Eight days before what would become known as the Six Day War, Israeli prime minister Levi Eshkol would go onto the airwaves to try and reassure a wary country. In the days and weeks leading up to his broadcast, Egyptian forces had closed off the vital Straits of Tiran, evicted UN peacekeeping forces from the Sinai and moved their own armed forces into the region. Simmering resentments from the first Arab-Israeli had resulted in years long border disputes between Israel, Egypt, Jordan and Syria. The unresolved Palestinian refugee dilemma mixed to create a tinderbox.

In the face of Egyptian and Syrian aggression, Israel's prime minister had urged restraint and caution in dealing with the military threat and had elected to await the details of a joint American and British plan to reopen the straits. Eshkol, already then known for his weak public speaking skills, delivered a stumbling and disjointed speech due in part to exhaustion and an inadequately prepared script. The speech would see public morale plummet and Eshkol would be pilloried in public and in the press. Ze’ev Schiff, a then columnist for Ha’aretz would exclaim, “It’s amazing how a people who suffered a Holocaust is willing to believe and endanger itself once again.” Not long after, Eshkol would be forced to reorganize his cabinet and accept the creation of a unity government which included the political opposition. Eight days later, Israel would launch its preemptive war, devastating its Arab opponents and achieving a crushing victory.

Israeli soldiers sit in front of the Western Wall in Jerusalem's Old City.

(Israeli Defense Ministry / Reuters)

Israeli soldiers sit in front of the Western Wall in Jerusalem's Old City.

(Israeli Defense Ministry / Reuters)

Although neither side actively desired war, and the major powers—the United States and the Soviet Union—worked to prevent it, the conflict ultimately unfolded. Israel, perceiving its core national interests to be at significant risk, found the assurances from its allies insufficient to mitigate the looming threat. Consequently, it determined that the danger was too severe to ignore and decided to initiate its offensive. Similarly, Israel sees its present situation vis a vis Iran as an overbearing national security threat particularly in light of the latter's relationship with Hamas and Hezbollah.

The brutal attacks of October 7th ended what may have been a perception of invincibility and spurred Israel’s government and population to concentrate its consideration of where the existential threats to the Jewish state ultimately lie. And given past Iranian statements and actions, it is unclear if Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu will decide to give diplomacy a chance or decide to go down the same route as 1967, deciding to act on its own regardless of what some of its allies might counsel.

In recent months, despite the ongoing conflicts with the three H’s: Hezbollah, Hamas, and the Houthis, Israel has grown increasingly vocal about the primary threat posed by Iran and its nuclear program. With Tehran’s uranium enrichment having approached weapons-grade levels, Israeli leadership faces a stark question: wait for an irreversible nuclear threshold to be crossed or preemptively strike Iran's nuclear infrastructure. For Israel, the stakes are existential. The possibility of airstrikes—either unilaterally or in coordination with the United States—is no longer a fringe scenario but a subject of active military preparation and political debate. From Israel's perspective, a nuclear Iran is not merely a strategic setback, but a potentially catastrophic development that could alter the regional balance of power irreversibly.

Israel views Iran’s nuclear ambitions through the lens of national survival. This perception is deeply rooted in Israeli security doctrine and historical memory. The "Begin Doctrine," articulated after Israel's 1981 strike on Iraq's Osirak reactor, establishes a precedent: Israel would not allow hostile regimes to acquire nuclear weapons. Iran’s ideological hostility, regional adventurism, and support for proxy militias such as Hezbollah and Hamas only deepen Israeli anxieties. The Islamic Republic's repeated threats against the Jewish state—whether rhetorical or material—reinforce the belief that allowing Tehran to become a nuclear threshold state would leave Israel vulnerable to coercion, or worse.

The collapse of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2018, due entirely to Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw from the treaty, resulted in Iran’s subsequent ramp-up of uranium enrichment at facilities like Natanz and Fordow add further urgency to Jerusalem's calculus.

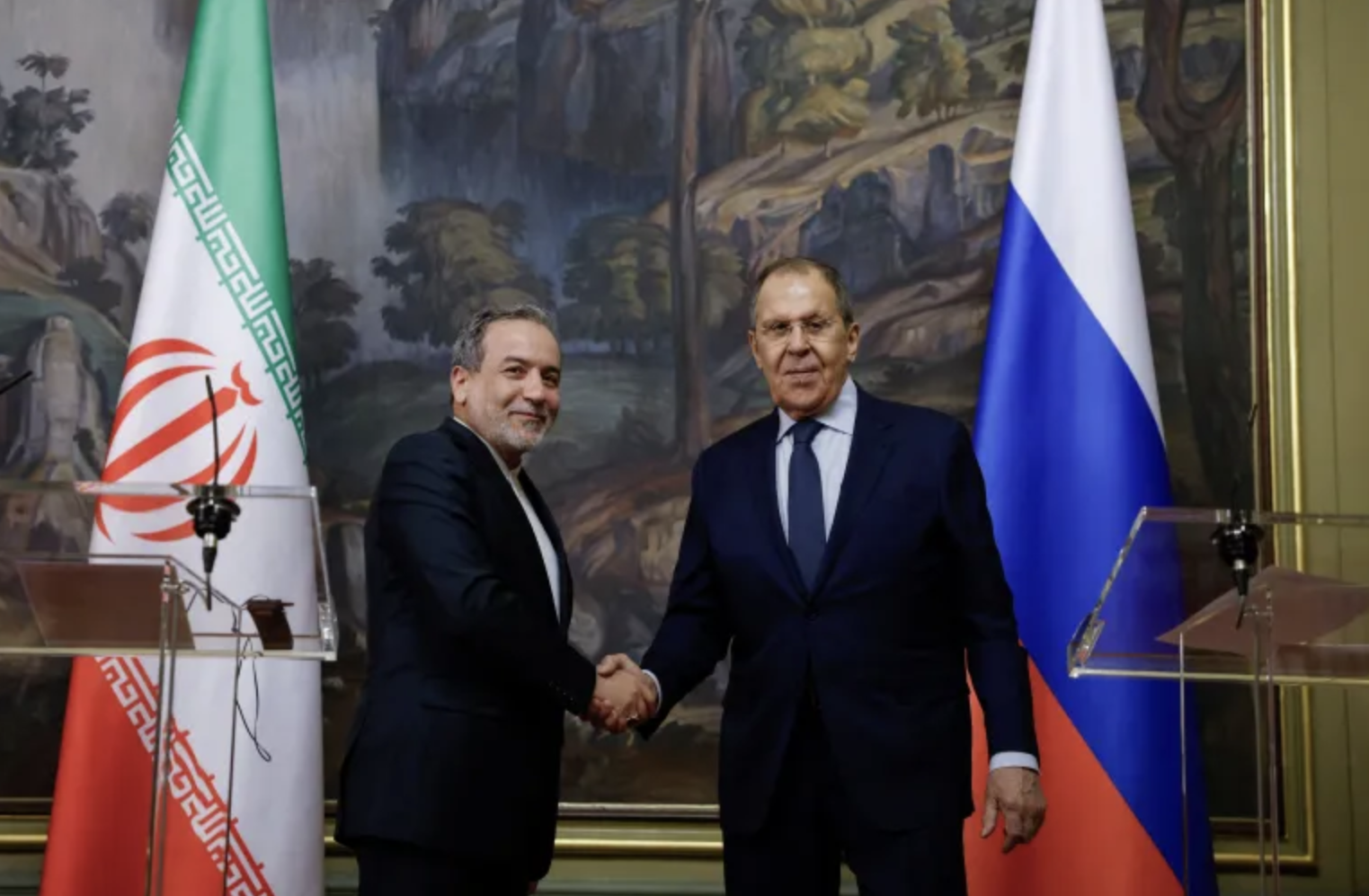

Russia's Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, right, and Iran's Foreign

Minister Abbas Araghchi shake hands during a meeting in Moscow, Russia,

on April 18 [Tatyana Makeyeva/Reuters]

Russia's Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, right, and Iran's Foreign

Minister Abbas Araghchi shake hands during a meeting in Moscow, Russia,

on April 18 [Tatyana Makeyeva/Reuters]

The military option is fraught with challenges, but Israel has made significant preparations. The Israeli Air Force has invested in long-range strike capabilities, including refueling aircraft, advanced munitions, and cyber warfare tools. Military drills simulating strikes on distant, hardened targets signal growing readiness. Still, Iran's nuclear infrastructure presents formidable obstacles. Key sites are fortified, dispersed, and in some cases buried deep underground. A single, decapitating strike is unlikely to eliminate the program entirely. Additionally, any such action would likely trigger a wider regional confrontation, potentially involving Hezbollah rocket fire from Lebanon, missile strikes from Iranian proxies in Iraq, and economic fallout in the form of oil price shocks. Israel must weigh the tactical benefits of a preemptive strike against the strategic risks of escalation.

The question of U.S. involvement further complicates Israel's decision-making. While Israeli officials stress their willingness to act alone, there is little doubt that coordination with Washington would significantly enhance operational effectiveness. U.S. capabilities in aerial refueling, intelligence sharing, and bunker-busting munitions could prove decisive. Yet the Trump administration has signaled caution, emphasizing diplomacy while maintaining the rhetoric of "all options on the table.", going so far as to block a plans for a joint American/Israeli strike this coming May. For Israel, this ambiguity is a double-edged sword: it preserves deterrence by keeping Tehran guessing but also underscores the possibility that Jerusalem may have to act without American backing. From an Israeli strategic standpoint, the longer the U.S. remains indecisive, the greater the likelihood that Israel will be compelled to act unilaterally.

Domestically, the prospect of a strike is politically complex but not necessarily divisive. While there is debate within Israel about the timing and consequences of such an action, there is broad consensus across most of the political spectrum that a nuclear-armed Iran is unacceptable. The Israeli public, shaped by decades of conflict and the memory of existential threats, generally supports assertive measures when national security is at stake. Regionally, Israel would likely receive quiet backing from Arab states such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, which also view Iran’s nuclear program with alarm. These states may not publicly endorse an Israeli strike but could provide logistical support or intelligence cooperation. On the international stage, Israel would have to brace for diplomatic fallout, especially from European allies and international institutions, but could mitigate criticism by emphasizing its right to self-defense.

Israel’s consideration of a potential strike on Iran may well not be a product of belligerence but of strategic necessity. Convinced that a nuclear Iran would upend the regional status quo and threaten its very existence, Israel seems prepared to act if it believes no other options remain. The window for diplomacy is narrowing, and with each passing day, the threshold for military action lowers. Whether Israel ultimately decides to launch a strike will depend on a complex combination of intelligence, diplomacy, and geopolitical timing—but from Jerusalem's vantage point, the clock is ticking.