While I am a licensed attorney, this is not paid legal advice. Nothing in this article is intended to create an attorney-client relationship. Unless expressly stated otherwise, nothing contained in this article should be construed as a digital or electronic signature, nor is it intended to reflect an intention to make an agreement by electronic means.

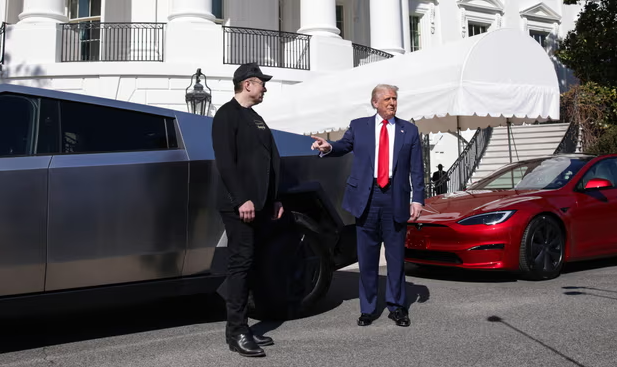

Elon Musk’s quick rise to grand vizier of the Trump court has brought with it the ire of almost every corner of the public. Whether he’s annoying gamers with fake cred, gutting random parts of the government that he doesn’t understand, or, allegedly, making up sales numbers incurring investigation by the Canadian government, Musk just can’t catch a break. His two flagship companies, SpaceX and Tesla, appear to have similar luck. His most recent starship prototype broke up in atmosphere; and recent Tesla numbers have revealed a steep descent of car sales in almost every region they are sold. Whether this is the reckoning of long term trends coalescing in an inevitable outcome, or a public response to Musk’s actions within the US government, and foreign politics, is up for debate.

Instead of Musk taking any responsibility as CEO for these numbers, rumors of a boycott on Tesla Motors have spontaneously appeared in the public discourse. A boycott that Trump, Musk, and Conservatives on the internet are convinced exists and is the sole source of Tesla’s woes. Not only does this boycott definitely exist, but it is also illegal according to Trump.

While signs of a political organization, non-profit, or even a discord channel coordinating or calling for this boycott are yet to be found, there are many news sources asserting that this boycott is entirely legal. NBC, Rolling Stone, and the Guardian all state with confidence that this boycott is totally legal and actually is protected by the first amendment. Lacking from these articles are any evidence of a boycott, explanation of what makes a boycott legal or not, and whether legality is even appropriate to discuss if this Tesla boycott does exist.

Annoyed by the poor discussion around the topic, I will attempt to provide a short legal overview of boycotts, when they are protected, and whether Musk is the victim of an illegal global conspiracy to make him personally feel bad.

While “boycott” may be a term used in common parlance, it has a specific meaning in a legal context. A boycott, also referred to as “concerted refusal to deal”, is an agreement among a number of economic actors to sever or limit economic relations with another economic actor or actors. Put more plainly, coordinated action by people or businesses in a market to harm or change the behavior of a business or businesses.

Boycotts are generally classified into three categories:

In 1890 the Sherman Anti-Trust Act was passed and formed the basis of all modern antitrust law in America. Section 1 of the Act makes any contract or conspiracy to restrict trade illegal, this has been interpreted to include boycotts as described above.

The majority of courts agree all commercial and almost all economic boycotts are always illegal. Noneconomic boycotts are a difficult category, some courts arguing they should always be illegal, others saying they can’t be illegal. Recently, courts have preferred to apply the “rule-of-reason” test when examining a noneconomic boycott. This means that these boycotts are evaluated on a case by case basis, to see if the restraint on trade caused by the boycott will be “significantly anticompetitive in purpose or effect.” More directly, courts must weigh the government’s interest in preventing anti-competitive pressures on a market against the rights of the members of the boycott. It is important to note, while not irrelevant, harm to the target of a boycott is far less important than the anticompetitive effects on the market in this analysis.

The common law has always recognized peaceful boycotting by collective members of the public to have some level of constitutional protection, even if the boycott would otherwise be illegal. Most often implicated are the right to petition and the right to expressive conduct, both derived from First Amendment protections. When weighing these rights in the context of a boycott, the goals, execution, and target of a boycott are scrutinized. Boycotts aimed at improving public life, influencing government action, or punishing companies or industries perceived to be committing a moral wrong, are all more likely to be found legal. Courts have also shown sympathy if the boycott is the only, or the most effective, method of expression that the group could meaningfully employ. However, any violence, whether for enforcement of behavior by members or enacted on targets by members, immediately forfeits any protections. Additionally, targets and methods of such boycotts often are required to be directly related to the goal of the boycott itself.

Currently, it’s not clear if there are any participants in a boycott of Tesla. Boycotts require interdependent, not independent, actions between the actors. Interdependent actors are ones who can only explain their actions by their coordination with other members. Actors who act in parallel, but commit such actions only based on their own decision to do so, cannot make up a boycott. Musk has given any number of reasons for people in the US, UK, Germany, and most other nations, to independently not want to buy his vehicles.

Assuming a boycott could be found, and members be brought to court, Tesla would likely be unable to show that the boycott is commercial or economic in nature. There is no profit to be gained by the members of the group, nor is there an economic but non-commercial benefit. Meanwhile, there are any number of noncommercial justifications for the boycott, punishing Musk’s behavior, pushing for his ejection from the US government, the company’s allegedly illegal sales reporting to abuse environmental grants. These and more are almost certainly valid public interest targets, to evidence a noncommercial boycott.

Assuming there is a boycott, and the Court finds it to be noncommercial, would it survive a “rule-of-reason” test? Well... this is where the optimism ends. Antitrust opinions often have the same feeling as those in constitutional law. Everything is vague and amorphous, until it is not. You have clear tests, until the tests actually mean something else. When it is time to balance interests, every judge has a different set of scales. Cases with almost identical facts, applied to the same tests, in neighboring jurisdictions resulted in opposite outcomes. This is most true when dealing with noncommercial boycotts.

A SCOTUS decision from 1982 is often trotted out regarding public protest and boycotting. Those unfamiliar with the field like to claim that the SCOTUS has put this issue to bed, something something first amendment + boycott = legal. While not irrelevant, the decision is far from controlling, or that simple. The facts in this case are not easily compared to the Tesla boycott, and antitrust courts notoriously have made decisions that fly in the face of SCOTUS opinions. Remember, a noneconomic boycott’s best day in court places it in a “rule-of-reason” analysis that forces the court to evaluate it on a case by case basis. There is no guaranty how a judge might evaluate these very complex facts and laws. Despite what some may tell you, boycotting as a protected form of protest, especially in the current political and judicial climate, is not a foregone conclusion.

If a court found the boycott to be legal, and assuming the SCOTUS doesn’t swoop in to grant Musk everything he wants, then Tesla’s legal recourse would largely be over. If a court instead found the boycott to be illegal, what’s the worst that could happen? The US judicial system would become the single greatest car salesmen by forcing the defendants to buy a Tesla? Jokes aside, one remedy for boycotts is an injunction against organizing and maintaining a boycott. In this case, an injunction against the members of the boycott’s speech encouraging or supporting the boycott of Tesla motors.

With this injunction against speech in mind, Trump and conservative voices claiming an illegal boycott exists with no evidence begins to make sense. This, and other legal strategies, by this administration, are being rapid fire created and tested in the courts, in an attempt to infringe on the rights of Americans and American businesses. While a court might try to tailor such an injunction to be narrow, the Administration would almost certainly apply it without abandon. Any public statement critiquing Tesla, or Musk, or the Administration that Musk is a part of may be interpreted by this administration as support of this illegal boycott, and therefore must be silenced. Ending any boycott that may or may not exist is of little concern to Trump and his administration, the real prize may be a veneer of judicial approval to silence their detractors.

The boycott that Trump and conservatives are crying about almost certainly does not exist. However, that does not mean they cannot gaslight themselves, and the public, into creating one, and use this fiction to enact their authoritarian goals. An enemy you create is far more useful than one you actually have to fight, and the laws surrounding boycotts are so loose as to create an opportunity to further expand their authoritarian control.

Please keep in mind that this is a very brief primer on boycotts and the field of antitrust law. This article was written to be informative to nonlawyers, not as legal advice. Below are some very well written articles from brighter minds than me regarding boycotts and opinions that have shaped how courts view them.